PHOTO: Author Elizabeth A. Havey, whose fiction captures the emotional heart of motherhood and memory with lyrical depth and powerful storytelling.

For this interview, I was contacted by a woman who works for a magazine in London. It was fun, though I am not a celebrity in any context, and this book happened a few years ago. But, I AM A WRITER, and thus I am sharing the interview with you.

Exploring Life, Love, and Legacy Through Stories That Resonate

Elizabeth A. Havey shares how her experiences as a mother, nurse, and Midwesterner have shaped her emotionally rich fiction, particularly her short story collection centered on the complexities of motherhood.

Elizabeth A. Havey writes with a voice shaped by a life deeply lived and beautifully observed. With every story, she invites us into intimate, powerful portraits of women—mothers, daughters, wives—capturing their joys and losses with unflinching honesty and lyrical precision. Her work pulses with emotional truth, grounded in both her literary training and her years spent as a labor and delivery nurse, a role that gave her firsthand witness to life at its most raw and miraculous.

Her recent collection, A Mother’s Time Capsule, is a testament to the complexity and resilience of motherhood. These are not sentimental tales, but layered narratives that explore memory, grief, strength, and love. Havey’s ability to infuse her fiction with her personal experiences—whether growing up in the Midwest, raising her own children, or tending to women in moments of profound vulnerability—gives her work a richness that lingers long after the final page.

We are honored to feature Elizabeth A. Havey in this issue of Novelist Post. Her candor, wisdom, and dedication to the craft of storytelling serve as a beacon to both readers and writers alike. In the interview that follows, she shares not only her creative process, but also the inner life that fuels it—a life committed to words, memory, and the enduring power of human connection.

Havey writes with grace, wisdom, and emotional depth, transforming life’s quiet moments into unforgettable, beautifully crafted literary experiences.

What inspired you to focus your short story collection on motherhood?

When I decided to create this published work, I looked for a common theme. I had written three novels, unpublished, but mothers were always major characters: the mother of a missing child; the pregnant women longing for birth; and my own mother’s death, she being widowed early on with a six, three and three-month-old.

How did your background in English literature influence your approach to storytelling?

When you spend hours reading for college classes, also taking a book with you for a doctor appointment, train or plane ride, and when driving you are listening to books on tape…it all inspires you to write. Also, many summers I attended the University of Iowa Summer Writing Festival, taking classes with published authors like Elizabeth Strout, the winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Olive Kitteridge.

“When you help a woman give birth…interesting characters come alive.” — Elizabeth A. Havey

What insights from your experience as a labor and delivery nurse found their way into your writing?

During every shift I marveled at the strength of my sex. When you help a woman give birth, try to ease her pain, encourage her…you drive home thinking about each patient, and for me only once did the infant die. I worked the 3-11 shift, driving home from Chicago to the suburbs. I had time to consider my day, my patients, their needs, and thus interesting characters come alive.

In what ways did studying at the University of Iowa Writing Workshops shape your voice as a writer?

Writing is a lonely profession, which can be great when it is just you and your characters coming alive on the page…but there are also questions. And even when you occasionally sit back, content as to how that chapter ended…it’s still only you as critic. You need incentive, someone to acknowledge your work is improving…that you have something to say, that your use of language has power and beauty.

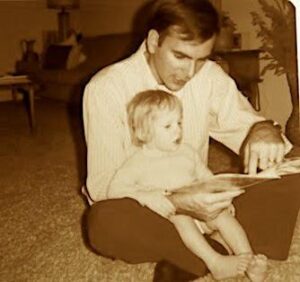

How do your Midwest roots continue to influence the characters or settings in your stories?

When you walk sidewalks of neighborhoods that have been in existence for over a hundred years, you feel a weight, a permanence clinging to brick houses, rows of trees. And there is always the Rock Island Train, that when you were a child clacked, whistled across the street into your open bedroom window. There are family traditions, Christmas at Marshal Fields, church services blocks away…then much later you’re driving freeways to visit your mother, you now in a growing Midwest city, so that these things appear in your stories, metaphors for your life.

“Writers always need to know WHEN the story must end.” — Elizabeth A. Havey

Can you share a particular story from A Mother’s Time Capsule that was especially difficult or emotional to write?

It would be When Did My Mother Die? which focuses on memories connected to my mother Jinni’s death. The story echoes the last phone call I had with her closest friend, Lillian. Both women were in their late 90’s, but my mother had dementia, and Lillian so saddened by this that she no longer wanted to see my mother, preferring to cling to memoires, the vibrant, discussions they had about books, art. The story ends with a flock of birds, “heavy dark fruit” covering the branches of a tree outside my window…these birds…just as my last call with Lillian ended. Soon after, both women died.

How do you balance the emotional depth of your stories with the craft of short fiction?

Writers always need to know WHEN the story must end. Though FRAGILE focuses on an accident affecting not only one of the two daughters of Tess and Adam, but also the trust that must be part of their marriage, the reader requires a satisfactory denouement. Marriage with children always presents the possibility of pain, sorrow. Love increases the need for safety, security, but love can also be the healer when danger, pain causes cracks in the foundation of the marriage. FRAGILE required a lot of editing to provide a satisfying ending. The child’s eye has healed…but what really matters is a new, stronger bond of love that unites the family under an endless, endless sky.

What role has your blog Boomer Highway played in your development as a published author?

Well I’m smiling…because the blog started with the name Boomer Highway, and my life did feel like a busy highway…a daughter in upstate New York getting her Master’s Degree; a daughter moving to California to work in the film industry; our son, still in grade school, because I’d convinced John if we had another child when I was in my early forties…it would be a boy. You dream, plan, are blessed…and then decide you have a lot to say. I was writing novels, but blogs were the thing…a way to write AND publish. Previously, I had published short stories in small magazines, been rejected by one university publication, accepted by another. And I was writing novels. I have written three, all unpublished. But Boomer needed a name change. It now appears every Sunday as: https://elizabethahavey.com

But because technology changes, I have a tech helper. In 2023 that person died suddenly, and days later the blog disappeared. I could not access my work. This affected other bloggers, we eventually discovering that without telling us, this woman had sold our blogs to some group in Asia. Details don’t matter; these people wanted me to buy back MY WORK. I struggled with what to do…then a few days later the blog reappeared. I stayed up all night copying most of my work into WORD…then telling them to TAKE A HIKE. I then had to start all over…a difficult time.

“Keep writing, there’s no magic to the process; and rewrite.” — Elizabeth A. Havey

How has being a part of Women’s Fiction Writers Association impacted your writing journey?

WFWA has been part of my journey. After my mother died, we moved to California to be near our grandchildren. Then on the computer, a notice: some writers are forming a group to provide a place to critique each other’s work, help each other publish…interested? I joined immediately and love being a beginning member. Though I have not yet achieved all my goals, the group has aided my writing, the friendships being part of my journey, the retreats, lectures and workshops improving my work. Have others gone on to be more successful than me? Yes. But I still believe in my work, though maybe what I write is more literary than that of others. At the end of the last WFWA retreat, which was in Chicago, I began to chat with two women who were also lingering. Immediately, we felt such comradery and now monthly exchange each other’s work on Zoom. In the writing world, you just never know who will be there for you.

What advice would you give to emerging writers who are trying to find their voice and stay committed to their craft?

Keep writing, there’s no magic to the process; and rewrite. Though I have written three novels, only sections have been published. Writers are explorers, discovering what to say, how to say it. Paraphrasing F. Scott Fitzgerald…So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.” That’s writing…preserving memory on the page.