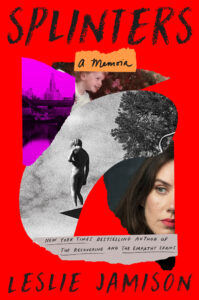

Leslie Jamison is a contemporary voice we must listen to. Compared to Joan Didion, Susan Sontag, her ability to touch us where we also live, her insistence that she explore challenging material, makes her more than just readable. Moving forward with material that challenges, her most recent publication requires she reveal an even more personal viewpoint.

In her first memoir, Jamison turns her unrivaled powers of perception on some of the most intimate relationships of her life: her consuming love for her young daughter, a ruptured marriage once swollen with hope, and the shaping legacy of her own parents’ complicated bond. In examining what it means for a woman to be many things at once—mother, artist, teacher, lover—Jamison places the magical and the mundane side by side, but that juxtaposition is always a surprise: pumping breastmilk in a shared university office; driving the open highway in the throes of new love; growing a tender second skin of consciousness as she gives birth to her daughter, watches her begin to live in this world. The result is nonfiction, but like no other. I present some of her work here.

JAMISON, A MEMIOR

Jamison starts by recalling the words she used to discuss the birth of her daughter. “When they got her out…” She writes:

“…the day after my daughter’s birth, I found myself emphasizing how much I held her, how I never wanted to put her down. It was as if I felt the need to compensate narratively for that first hour, when I wasn’t able to hold her at all—to insist that we bonded just as much anyway. I found myself exaggerating the part about the not caring if I was numb before they cut me open, when in fact I did care. I told the doctors that I would actually love some more anesthesia in my epidural…as if I were trying to make up for other kinds of pain I didn’t experience: unwittingly obeying the cultural script that insisted on suffering and sacrifice as the primary measure of maternal love.”

Jamison says that even now, 3 years later, when women describe pushing out their babies or having 40 hours of labor, she feels a pang of guilt, maybe even shame, as if her own birth story “wasn’t one that merited pride or celebration, but was instead a kind of blemish, a beginning from which my daughter and I must recover.” She then relates to us the fascinating history of the Caesarian section. A few excerpts: French obstetrician Jean Louis Baudelocque wrote: “That operation is called Caesarean by which any way is opened for the child other than that destined for it bye nature.”

JULIUS CAESAR–AH, THAT’S WHERE WE GET THE NAME

There is an apocryphal story that Julius Caesar was born by cesarean, as his mother survived the birth and went on to bear more children—at a time when it was impossible to survive a C-section. Jamison writes that in 1925 Herbert Spencer, a professor of obstetrics at the University College London, speculates that it “was called Caesarean as being too grand to have been first performed on ordinary mortals.” He also calls it: “the greatest of all operations, in that it affects two lives.”

But Jamison knows and we know, that for most of history, the procedure saved only one life, and it wasn’t the mother’s. Not until the 20th century did the mother survive, Before that, it was usually used as a last-ditch effort to save the child, the mother dying, bleeding out, or already dead.

MACBETH, A FORETELLING

Historically and in literature, the C-section was often associated with the imperial, the divinity. In Shakespeare’s Macbeth, the cesarean-born Macduff experiences a birth that is an answer to a riddle: The witches have promised “that none of women born shall harm Macbeth” but in Shakespeare’s creativity, Macduff is exempt from such a foretelling as he “was from his mother’s womb untimely ripped.”

Jamison, a modern woman looking back on the history of a procedure that she has experienced, makes the comment that Macduff’s exceptional birth might grant him some singular power, but such a birth also relates monstrosity. “Untimely ripped doesn’t exactly summon the epidural and the blue tarp.” Jamison knows, she’s been there.

COLONIAL AMERICA

Of course, the early history of the Caesarean, a little used and experimental procedure, did not insure life for either the infant or the mother. But neither did natural childbirth. The baby was often fortunate if he or she survived.

But in the graveyards of Boston and other parts of the New England states, where our early settlers are buried, you can often find a series of graves for a family. First is the grave of the husband, his dates, which always extend his time of life. Then alongside him are his wives—sometimes two or three. No, he wasn’t a bigamist, but when the first wife died in childbirth or from puerperal fever (see below), he married again. And if that wife died, he married again—eventually not for sex or more children, but for someone to raise his progeny, feed and clothe them, tend to his garden.

THE SHAME FACTOR

Jamison also discusses how the advent of the C-section has been used by some to shame mothers. In his book, Childbirth Without Fear, Grantly Dick-Reed inferred that pain during delivery was a lesson women needed to learn. “Children will always mean hard work and will always demand self-control.” Easy for him to say when he’s standing by the delivery table and not lying on it.

FINAL THOUGHTS

Jamison’s writing is pivotal…she has much to say to women as she works through the angst of her own fears and regrets. Her work speaks truth for all mothers, no matter how we have brought our children into this world. Jamison: Why do we want so much from our birth stories? It’s tempting to understand life in terms of pivotal moments, when it is actually composed of ongoing processes: not the single day of birth but the daily care that follows…diapers and midnight crying, playground tears and homework, tantrums…If we are lucky, birth is just the beginning. The labor isn’t done. It’s has only just begun.

(This post has been adapted from an earlier version; with the loss of my blog, I was fortunate to recover some of it.)

4 Responses

So sad, especially about the grave of a family with one man and several ill-fated wives. Having had two rocky deliveries, I assume I wouldn’t have survived child birth, had I lived earlier. So sad. Women always go through so much.

Thank, Laurie. I so appreciate your point of view. Always, Beth

We need more books by writers like Jamison, if for no other reason than to bury those written by such as Dick-Reed.

Wonderful article, Beth!

Wow, Diane, thanks so much. I try to find pieces that support women, and their needs and worries. This

woman has it all going on. THNAKS AGAIN.